Fighting dust with better filters

How can the air in museums be improved to protect art?

With extreme caution, the cotton swab moves across the hilly landscape of the oil painting, freeing it millimeter by millimeter from the dust of the New York city air. Now it is time to hold your breath: Pablo Picasso’s “Flower Vase” is on the restorers’ table in the Museum of Modern Art. Even the slightest mistake could ruin this precious painting – no trivial responsibility. Slowly, the restorer sets the swab aside and breathes deeply to calm his nervous hands. All the energy needed for total concentration has been used up. For today, the dust has won.

Attempting to battle the dust of a city using only a cotton swab is of course nonsensical. The restorers’ work takes place in cleanrooms far away from the crowds; but as soon as the Picasso is back on display, it is exposed to the ambient air. This is where we need to start. In the heart of Manhattan, dust pollution is high and extremely dangerous for the artworks. Because there is much more to what is suspended in the air than can be seen with the naked eye.

In large cities such as New York, the ambient air is composed of numerous different components.

In large cities such as New York, the ambient air is composed of numerous different components.

Not all dust is the same

Most of the restorers’ work involves removing normal house dust from the Picasso: i.e., heavier particles larger than 10 microns, which settle more quickly due to their weight. However, metallic dust particles make cleaning more difficult; their sharp-edged surface can easily scratch the exhibits. House dust itself not only looks distracting. Due to its hygroscopic and mostly acidic properties, it can easily accumulate moisture and cause corrosion of metal or acid-sensitive materials. Smaller particles of 0.1-2.0 microns, on the other hand, do not settle so quickly. They remain in the air as suspended particles, where they also bind and transport pollutants.

Dirty ambient air

The composition of the suspended particles is directly related to the environment. The city air of busy 53rd Street, in front of the Museum of Modern Art, mainly contains pollutants from combustion engine exhaust gases: tiny particles that adsorb harmful gases such as sulfates, nitrates or ozone and accumulate in the outside air. Ozone is a strong oxidant and causes decomposition and brittleness in paper, textiles and rubber.

Dirty art

Although ozone decomposes rapidly indoors, this process produces organic acids, aldehydes and ketones, which are themselves classified as air pollutants. Along with these pollutants, the composition of the suspended dust inside the museum is complex. It is formed from a combination of reactions between the exhibits and general dust inside the museum, as well as the particles that visitors bring with them: skin particles, fabric fibers or gases from the air they breathe.

When restorers securely sealed textiles in airtight foil, they noticed that artworks produce pollutants even without air supply. Even though the exhibits were protected from external influences, the materials of the pieces reacted with each other so that volatile acids accumulated, leading to their condition deteriorating. Instead of airtight sealing, the right solution is a constant exchange of air. This dilutes pollutants produced in the museum and thus protects the artworks.

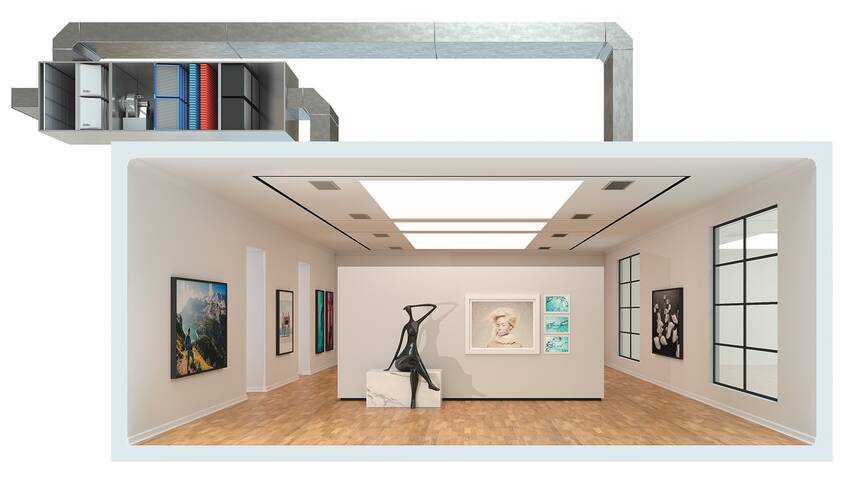

Sophisticated supply air

To avoid new pollutants entering the museum from the outside, sophisticated air conditioning and ventilation systems are required. These must filter both harmful gases and particles from the supply air as well as having a long service life. For this to be achieved, the sequence and selection of the filters used is crucial. The more efficiently an air filtration system is designed, the less dust is introduced from the outside air.

Innovative solutions readily available

There is no uniform limit value above which pollution becomes a serious threat to exhibits. The requirements of the artworks are too varied and the composition of the air pollutants too individual.

Thanks to the innovative and precisely tailored filter solutions for ventilation systems with upstream ePM10 (M6) fine filters from Freudenberg Filtration Technologies, dust is not only kept away from Picasso’s “Flower Vase”. The system also includes downstream filters such as cassette and HEPA filters of classes E11 to U15. These enable the reliable separation of particles with a separation efficiency of more than 95 percent and provide conditions similar to those found in pharmaceutical cleanrooms.

The flowers that Picasso once used as his subject have of course long since withered. But thanks to ingenious filter systems and the work of the restorers, at least his painting will far outlive him.

Language / Country

Language / Country